A FISHING LIFE IN SCOTLAND.

By Jim Ferrier

My family – father and uncles – were keen fly fishers and its little wonder that I followed the family trend.

A typical ‘cast’ would consist of a Peter Ross on the tail, one of the woodcock series, red early in the season and green by mid-summer, the obligatory Greenwell Spider next and a Bloody Butcher on the bob. Size 14 was usual but size 16’s were used on occasion.

For heavy and coloured water, a common occurrence in the Borders, a Partridge and Orange or Snipe and Purple spiders were alternatives, and a Dark Mackerel often replaced the Peter Ross. Sometimes, for a change, a Blae or Grouse series in the bigger waters such as the Tweed would be used.

Dry fly was not part of the fishing scene and was considered to be ‘too difficult’, and unnecessary, and somewhat effeminate. It was ignored as a result.

Natural gut casts were used. These were tied from short lengths of about 12”. This was a time consuming rigmarole performed the night before the trip. The cast had to be tied meticulously with dampened gut as it was quite brittle in the dry state. Each knot had to be tested thoroughly. The finished cast would be reverently laid in a damp carrier for use the next morning.

The modern proliferation of lines – floating, intermediate, fast and slow sink and shooting head that we accept today – was unknown. There was, to us at least, only one option – a Kingfisher silk line. Expensive, difficult to maintain, it required cleaning and drying after each trip and redressing before the next. The Kingfisher was handled with loving care, but a couple of seasons was about its life.

Cane rods, preferably by Hardy Bros., were the ultimate “weapon of choice”. My father’s Hardy was his wedding present from my mother, and this was treated with due reverence. I don’t think that I was ever allowed to fish with it. It weighed a ton, cast like a piece of spaghetti and was exhausting for the tyro but for boat fishing in true loch style it was perfect.

Lesser mortals like myself had to make do with a battered greenheart which had a decided bow in the middle section, loose ferules and a repaired tip. It also was heavy and had no ‘spine’. Casting was a real trial of strength and casting into the wind was impossible.

All rods were expensive and treated with kid gloves; were cosseted in special bags. The Hardy was revarnished each season until the whippings could hardly be felt and the ferules and rings inspected and professionally replaced as needed – which was often.

I was brought up on this system but always with hand-me-down gear, flies, rods and lines.

The local river was the North Esk – how this name keeps cropping up! It flowed from the Pentland Hills through the local laird’s estate. The Fishing Club made him an honorary member, and, in return, we had the privilege of fishing the river in the estate, – though not his ponds which he retained for himself – rainbows and all.

The Esk was small, fast and rocky, and would descend in spate with any sort of rain. It was full of small trout about three to the pound. They were lighting fast at taking and rejecting a fly but as it was a 15-minute ride by bike from home, I haunted the place.

Each pool became well known and so did the position of the fish. Even with four flies, these trout could be very fussy. I think it was nearly a year before I could consistently land fish.

My first trout is remembered even now. Taken on a Snipe and Purple under overhanging bushes and weighing just less than half a pound. I see it in my mind’s eye even today and I could go back to the exact spot if asked.

The excitement of taking it home in triumph, to be rolled in oatmeal and fried. Food of the gods!

About this time, we made a pilgrimage to Black Haugh, far into the Cheviots on the Caddon Water. My great aunt was the teacher in a one-teacher school. She lived with her sister many miles from Clovenfords. It was an expedition of some magnitude as we started by bus, then steam train and finally taxi. I was fully kitted out to fish with the trusty greenheart, box of casts, flies and unbounded enthusiasm.

A steam train was a highlight of any trip and the station master of the very small Eskbank station came forward to discuss in detail where I was going and how to fish. I had met a fishing enthusiast. We discussed what would be “on the water” and what fly would be successful, and he gave a lot of advice about Caddon Water.

On the return journey, my Station Master friend was collecting tickets and he hailed me as a fellow angler. The trout was retrieved, all dried up and hollow eyed to be admired. A blow-by-blow account was given, and I was congratulated on the size of the fish and my skill. This was heady stuff for a small boy fishing on his own for the first time.

The elder members of the family and friends made day trips to the Tweed and the small fry were not welcome to these jaunts. A decisive limitation was the licence cost of five shillings per day, an enormous sum to a schoolboy in 1945. The Tweed had sections with exotic names like the Velvet Haugh, Cardrona and Ashiesteel. At the right time of the year there was a chance, admittedly a very slim one, of a salmon.

Fishing the Tweed for trout was a different proposition to the Esk. To begin with, gumboots were useless and an investment in thigh boots was needed. A combined Christmas and birthday present supplied them.

Then there were other anglers – we rarely met another fisher on the Esk. The traditions and etiquette of the Tweed had to be learned and learned fast and if you stepped out of line, you were very quickly and decisively made aware of your error.

These protocols would stand in good stead today in Tasmania.

Finally, because of the ‘big’ water, its depth and its currents, casting had to be that much better tho’ it was still “across and down”.

The first trip to Ashiesteel was an adventure in itself. We went the 30-odd miles in my father’s car – a 1934 Rover – and I was consigned to the back seat. It was uncomfortable and cold but nothing like that could spoil my fist trip to the Tweed and be accepted as one of the party.

In those days, the trout averaged about three quarters of a pound, but occasionally a bigger fish would be caught. If it was in excess of a pound, it would become the talk of the club and all its details would be discussed – where and in what part of the pool, what was it taken on, what time o’day and, most important, what fly. A fish of two pounds would make the local newspaper and even a photograph would be included. This was fame indeed!

Because the fish were significantly smaller than their Tasmanian counterpart, it didn’t follow that they were easy. In the Esk, the trout saw few anglers and fewer flies and they would flash at anything which appeared edible but, on the Tweed, the fish were very sophisticated. During the week but more so at weekends, they were fished over by scores of anglers with all sorts of lures, bait and flies. It followed that if you got your half dozen of three-quarter pound trout you could feel well satisfied.

The great curse of all Tweed fishers was the “trotters”. These were busloads of so-called anglers from mid Scotland. Two were off loaded at the head of each run or pool and then they floated a worm under a float down the current ‘trotting’ alongside the float as the water was searched. Woe betides if you got in their way. They would certainly walk over your gear and you too if you didn’t get out of the way.

The final ritual when fishing the Tweed was the stop at a hostelry on the way home. The junior members were left in the car while the adults “went to see a man about a dog”. We never did see this dog but when queried, it was always deficient in some way – ‘its tail was too long’ or ‘it didn’t have enough spots’ were common problems to the canines of the Borders!

The North Esk remained my primary water. It was close by, and, by biking, I could fish several miles usually without seeing another soul. The across and down method had its limitations as many of the better pools were not approachable or fishable by this method.

I was bemoaning the fact to an old pensioner, Dargy Ellis by name, who could fish only the closest pools to which he could walk. He showed me his bag. I was astounded. He had fish when I had none and the size was significantly better than my norm. He was fishing “Dry Fly”, that mystical effeminate method ignored by the family.

He showed me The Fly – Blue Hen and Yellow – and tied me half a dozen. He also made some floatant from candle grease dissolved in hot liquid paraffin. Poured into an aspirin bottle, with a feather to anoint the fly. He sent me on my way with the secret of secrets, hitherto unknown, you fished upstream!

This opened an expanded world of fishing. Soon the fly box contained new flies; March Brown (still a favourite fly in Tasmania today), Iron Blue Dun, with the tail removed so that it sat on the water with the body dangling under the surface (Emerging Midge?), Black Spider and, of course, the ubiquitous and ever ready Greenwell Spider and the Blue Hen and Yellow.

Fly tying then became an obsession and with the help of the aforesaid Laird’s keeper, I never went in want of Rooster hackles, Partridge and Grouse feathers and exotics such as Heron. Rabbit, Hare, Deer, all became available in due course and occasionally, my keeper friend would whisper the “the laird and his lady” were away for the evening and I could fish the prized ponds.

In fact, the largest trout I ever caught before coming to Tasmania was a Laird’s fish of just on two pounds taken in the gloaming while the Laird attended a concert in Edinburgh.

My father and uncles were also keen loch fishers, always from a boat. Again, this was a different technique where wet flies were cast downwind from the drifting boat. They were dribbled back so that the bob fly just bounced through the waves.

This was traditional loch style fishing with a near floating line and the flies never moving more than six feet. I was introduced to this type of fishing on the hill lochs close to home when a half crown surreptitiously changing hands with the water bailiff, ensured an evening’s fishing.

The boats were wooden, big and heavy and no outboards were allowed. They ‘held’ the water and drifted well and were stable, but they were heavy to row. I was now welcome to fish with the adults. Tho’ in retrospect I’m sure it was for my rowing skills rather than my fishing prowess.

We had favourite local waters and preferred drifts on these waters. Even though we fished different flies my father and I would end the season with almost the same number of fish caught.

The holy grail of loch fishing in Scotland was undoubtedly Loch Leven and our club had a standing order for six boats five times a year. This allowed 18 anglers to fish and the competition for places and fish was keen.

The Loch Leven boats were wooden, 18 feet long, very heavy and good ‘sea’ boats. They allowed three anglers to fish comfortably and turns were taken to be ‘the middle man’.

Outboards were anathema on Loch Leven and two rowers were needed. Boatmen could be hired at a price (plus a bottle of whisky each) but this was too expensive for club members. So, once again, I was welcomed to the party provided that I rowed every leg of the drifts. This certainly developed muscles and blisters in short order.

The technique for fishing Loch Leven was the same as our local lochs. A strap of four flies would be cast straight downwind and retrieved quickly with the bob fly bouncing through the waves. “Wee doubles” in size 16 were popular and a typical cast would be Teal and Silver, Woodcock and mixed, a Winged Greenwell and a Bloody Butcher. Alternatives would be Peter Ross, Mallard and Claret, Black Spider and Kate McLaren.

We had favourite drifts. We would start at the Thrapple Hole and, provided the wind was right, down drift to the Castle Island. It was always planned to arrive at the Castle for tea and sandwiches and for consultation with other boats.

There were libations to the Loch’s gods and if the fishing was slow, flies would be ceremoniously dunked in the whisky before being consumed. Whether this achieved the desired result was never very clear, but it made the remainder of the day pleasanter for the adults of the party. For myself, I was back to being a galley slave at the behest of father and friends.

At the end of the day, all boats returned to the dock where the keepers would relieve you of your catch, take it to be weighed and counted, and the results set against your name on the leader board.

If you had had a spectacularly good day and you headed the score board, it would be announced in the weekend Scotsman Newspaper. You were always referred to as Mr….., with X fish; Y lbs.; Best fish, Z lbs., Greenwell and Grouse and Claret. During all the trips to Loch Leven, I never made it to the national press.

In those days Loch Leven was very popular and there was keen competition for boats. The club always booked a year ahead and if you didn’t take up your options, the chances of renewing them were slim. The size of the fish caught was remarkably constant over those years. They averaged just over a pound and showed the Loch Leven characteristic of slim and silvery.

The day finally closed with the bus trip home and suitable staging posts on the way – always without the small fry being invited to inspect the man or the dog, both of whom remained spectral – tail and spots notwithstanding.

Eventually the use of a push bike to access fishing curtailed the prospects and a motor bike was purchased. This was a 250cc, 1938 Royal Enfield. It didn’t live up to its reputation as reliable transport and it spent most of its life in pieces. In due course it was retired in favour of a 197cc Francis Barnet.

This bike increased my fishing range enormously to rivers such as the Lyne, Clyde, Manor Water, Talla Reservoir, Roseberry, Gladhouse and most important of all, Portmore. These latter waters were compensating lochs for Edinburgh water supply, and they contained some big fish – the attraction of course.

During the summer, Portmore had a hatch of enormous stone flies which lasted for about a week. The trick was to be waiting for these 50mm long ‘motor boats’ as they skittered for the shore. A Hairy Oobit was specifically designed just for these monsters and the fish which pursued them.

Eventually a car became essential when I transferred to Glasgow and a “Beetle” was purchased.

The Clyde reaches nearer Glasgow were heavily polluted and didn’t hold fish, but further upstream were attractive. After work a quick trip was often productive.

Motorised transport opened vast new fishing prospects and a trip to Caithness and Sutherland in the far north of Scotland became a main fishing event of the annual holidays.

Melvich was the centre and we stayed in the Melvich Hotel with its snug bar and its impressive array of whiskies. The local fishers frequented the bar where they talked in Gaelic – until we southerners arrived. Then they would speak in Scots English. We remarked to them that we didn’t understand Gaelic and we were not affronted but they insisted on speaking English as “it was bad manners in the present company if the present company couldn’t understand it”.

We arrived late Saturday and were met by the owner who advised that the previous week had been poor. This didn’t faze us as he was talking about salmon and on the Halladale River where the fishing costs for a beat were astronomical and well beyond our means.

We were interested only in trout and hence were considered lesser mortals of little account. We were also advised that there was no fishing on the Sabbath – a rule that we adhered to religiously! This didn’t stop us checking out the various waters as we made plans for the Monday.

In the vestibule of the Hotel there was a board and the names of all the fishing guests were entered thereon. The guest at the top of the list had the choice of all the hotel waters and he duly recorded that against his name. The second on the list had the choice of the remaining waters and so on. As the new comers, we were at the bottom of the list, and we waited with some concern to see what was left to us.

Next morning, we found to our delight, that we had a choice of any and all the hill lochs. The salmon beats on the river were always in demand and there was considerable agonising on the part of the salmon fishers as they waited to see if they won a favourable beat.

We were given instruction on how to get to the first of the lochs and off we went. “Go up the peat road as far as the car will go”. Rough going but fine! “You will see a single fencing post on the edge of the hill and follow the track to it”. This was much more difficult as there were hills all round and we didn’t know if “the post” was near or far. After scanning the nearer hillsides, we thought that we saw it and, surprise, there it was – but it had fallen down, and it was half buried in the heather. We never discovered the “road”.

There opened a vista of flat, bare, treeless moor, generously pock marked with small lochans, all set in wet heather strewn peat moss. The land was very similar to Tasmania’s far Western Lakes, except that the kerosene bush was replaced with heather.

Our instructions again said, “Look directly south and you will see a marker standing in the heather. When you get to the post, Eaglais Mohr (the big loch of the church?) will be directly in front”. When we eventually found the marker, it turned out to be an old broken oar edge-on and almost indistinguishable against a heather background.

Nevertheless, there was the loch and the greatest surprise of all there was a very serviceable boat on the shore. It took about 90 minutes walking through wet squelching peat to reach our goal.

The technique was to fish standard four flies downwind from the boat with an emphasis on bushy flies which “moved water”. The Kingfisher Butcher, Blae and Black, Blue Teal and Silver, Kate MacLaren or Zulu were on every cast. As we rowed back upwind, the tail fly would be replaced by a tiny spoon and the rig streamed out behind the boat. The spoon took its share of fish on the day.

Once again, two fish to the pound and they were eager – that is, until they ‘went down’. Not another touch or swirl could we get.

We returned to Melvich to find a large white enamel tray in the vestibule and our fish were placed on the tray for all to see. The salmon fishers were scathing of the size and numbers, but we retorted that at least we had caught fish while they had flogged all day for nothing.

Next morning, we found that we had a choice of all the fresh water lochs again and off we went to Loch na Caorach. This was quite a climb but at least it was straight forward and well signposted. Again, a great day’s fishing for half pound fish and in those days numbers were important.

Our catch dominated the enamel tray at the foyer. As before, we had to counter the jokes at our expense.

The third day we decided to return to Eaglais Mohr but fish its much smaller sister loch Eaglais Beg. Beg meaning little. It had the reputation of holding “monsters”.

We had barely started fishing when a sea mist enveloped the whole area. It was cold and clammy, and the fish were totally unresponsive. After a couple of fruitless flogging hours, we decided to return to the Hotel.

We hadn’t packed a compass or maps and it was only when we attempted to retrace our steps, we realized that we were in a difficult and even dangerous situation. Luckily, a fog horn moaned forlornly at minute intervals and in the grey blanket, we at least knew north.

We set off full of hope and resolution and when we came to the first lochan which we were sure we had passed coming in, we realized that there were no foot prints on the sand. We hadn’t been there before. We stumbled on and we repeated similar lochan episodes several times, still walking north and listening to the fog horn to keep the direction correct.

After what seemed an age, we eventually came on to a very faint track – a disused access to some peat cuts. Following this down to a river, we realized that we had strayed off the plateau to the edge and into the next river system. We followed the river to the coast and hence back to the Hotel.

We had walked in a great semicircle always believing that we were taking the shortest and direct way back to the car. We managed to scrounge a lift to the car and the adventure finished without damage except to our navigating skills.

As we approached the Hotel, we saw one of the salmon fishers hanging – literally – about the foyer. He was in a merry mood, and it was quickly obvious that he had been celebrating somewhat too well in the snug bar. He had a salmon of about 10 pounds on the enamel tray and was “standing his hand” to all. He rested on his laurels for the rest of the week and didn’t fish again.

Driving in the Highlands north of the Great Glen was always exciting. Most of the roads were two strips of bitumen to suit tyre tracks with passing places set at strategic intervals. There was always that fine line when we met another car or lorry coming towards us. ‘Who should drop into the passing place?’ In practice we found that the local drivers were very courteous and considerate, and we never had a problem.

However, we did pull someone out of the heather at the side of the road once – not bad for a Beetle! The driver was almost inarticulate with rage. He turned out to be a senior judge of the Court of Session and he had been run off the road and he hadn’t got the registration of the car.

I had a feeling that the errant driver, if he had appeared before the Judge, would have been loaded with chains and ‘put away’ without the option, irrespective of his excuse.

Forty years later, after many years in Tasmania, I returned to Melvich Hotel and decided to recreate those halcyon days and adventure once again onto the plateau and walk to Eaglais Mor.

This time, fully armed with Ordnance Survey maps and a reliable compass, I took the track to the peat cuttings. However, it had deteriorated even more, and the fence post was nowhere to be found. A compass bearing gave the correct direction, but the land had been drained, conifer forests planted, and the whole scenery had changed. Distance seemed to have elongated greatly with time and the difficulty of walking was that much worse.

Yes, I found Eaglais Mohr, and I cast a line. I caught a fish but the magic of that bleak windswept landscape of the 1950’s was lost forever.

Back at the Hotel the owner produced the Visitor’s Book dating back to the 1890’s. The size of the fish and the numbers had not changed significantly but the anglers had.

Most, in those days were landed gentry with a smattering of senior army and navy men, titled visitors and the judiciary.

And then my company made me “an offer I couldn’t refuse” and I came to Australia. Thus, the first part of my fishing odyssey concluded and a new one began.

AUSTRALIA

I arrived at Sydney airport at 6.30am one morning in September 1963 clutching a small suitcase and a split cane fly rod.

As a commissioning and furnace engineer in Australia and New Zealand, my home base was Melbourne, but I spent much of my time in various parts of Australia and New Zealand with little time for fishing.

One bright spot was Canberra in 1965 during the commissioning of the new Australia Mint when, after work, I would take very rough Forestry Commission tracks to fish at Brindabella. Small fish about three to the pound but willing and active and often taken back to be fried for supper with friends.

Marriage and a family followed and once again, my fishing opportunities were limited. We made excursions to the Howqua River draining into Lake Eildon. Our trips seemed to be foiled by weather and we felt lucky to have survived the experience.

Then a position as metallurgist and combustion engineer at Comalco Bell Bay was offered and we transferred to Launceston.

This started a completely new chapter in my fishing history.

It wasn’t long before I put out feelers about fishing and I was very lucky indeed to meet up with Charles Peck. Charles had and still has, an encyclopaedic knowledge of Tasmanian fishing. With his help, I have fished many of the iconic waters both river and lake of Tasmania.

Charles introduced me to the Nineteen Lagoons – Augusta, Flora and O’Dell’s, Ada and Ada Lagoon, Botsford Double and First Lagoon and Lake Kay. Also the lakes at the western end of the Tiers – Explorer, Nameless, Lucy Long.

Charles and Marcia remain very close friends and I’m eternally grateful for his ‘tuition’ in all things Tasmanian. Charles introduced me to the Fly-Fishers Club of Tasmania, and I became acquainted with all the worthies of that Club.

Surely, Secretary Max Bertram holds pride of place. It is to Max that I had the opportunity to go to Penstock Lagoon for the first time and it was Max who dubbed me ‘The Laird of Penstock’.

The Fly-Fishers Club of Tasmania’s shack at Penstock was very basic and in need of much ‘tender loving care’. It was not suitable for family trips so I cast about to find if I could rent a piece of land at Penstock on which I could set up a caravan. My inquiries of the owner, John Alwright, didn’t produce a result and the idea died.

But I met a fellow Club member, Alan Miller, who, on hearing of my interest in Penstock, suggested that we combine and build two shacks for our families. My building skills are minimal but Alan, a skilled builder and carpenter, proposed that he would supply the knowhow if I laboured to him. In due course two shacks were built and completed with marvellous views of the Lagoon.

Alan is a long-term fishing friend valued for his skill and knowledge both building and fishing wise. Penstock became my piscatorial spiritual home for many years and still holds a special place in my fishing experiences.

Alan and I fished together every season for many years. We had 10-day epic trips in the highlands. Lake Sorel was a favourite destination and we, using the shacks as a base, fished long hours in the Nineteen Lagoons – Botsford, Kay, Augusta and further west.

As a member of the Northern Tasmanian Fisheries Association, I became the Government nominee to the Tasmanian Fisheries Commission. A very interesting job indeed. I still count many of the officers I met then as personal friends.

A 12-foot ‘tinnie’ and 15HP outboard was purchased and with Cliff Oliver we fished the highlands. A typical trip would start at the Cow Paddock at dawn and then transfer to Little Pine for just before lunch and ready for the afternoon dun hatch. Then back to the shack for a meal and a libation to the fishing gods.

About this time, a parcel of land near Birralee came on the market and the NTFA worthies, Stewart Scott, Don Gilmour and Ron Stevenson, appreciated its potential as a fishery.

The Four Springs Recreational Committee was formed with me as the Secretary. There followed many years of lobbying at both the Federal and State level before finances were obtained and the dam built. The water was officially opened by Nigel Forteath in 1999.

Four Springs is an early season fishery, fishing well when the weather of the early season in the Highlands deter all but the hardiest anglers. It is carefully stocked by the Inland Fisheries with mature trout to maintain quality fishing.

Since then, Nigel and I have fished Four Springs usually once a week during the season to robust and fit brown and rainbow trout.

We take the majority of our fish on a Black Nymph weighted with a gold tungsten bead head. An alternative is a Stick Caddis with a yellow head.

While at Four Springs, Nigel nets water bugs for the platypus at Beauty Point. Damsel nymphs form the majority of the catch with back swimmers and mayfly nymphs in season.

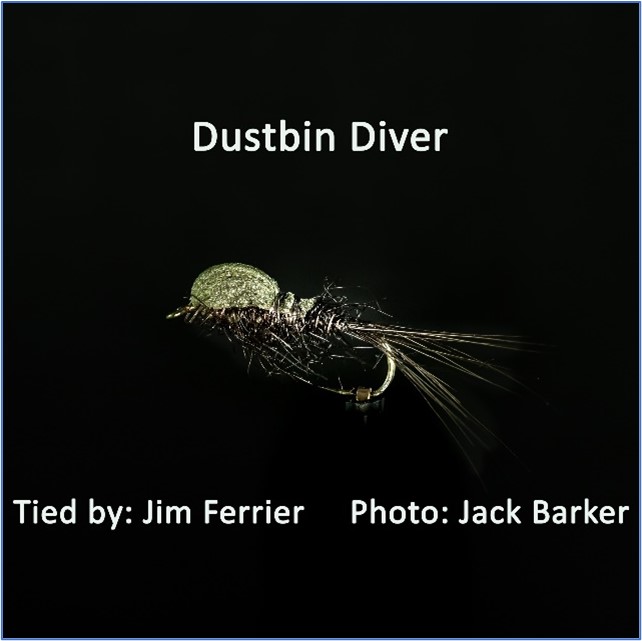

The Dustbin Diver.

This fly was developed in frustration for those difficult fish who were just sipping as the dun hatch had apparently started – yet a floating dun didn’t work.

This was particularly true at Little Pine. There were maddening days when we would cover fish with conventional dun patterns of all types and sizes only to be completely ignored.

And then we realized that it was the emerger that interested the fish, not the fully winged dun, and we tried several patterns to replicate the emerging action. Thus the Dustbin Diver evolved.

The Dustbin Diver.

Hook: Partridge Size 12, 2X long shank.

Head: Black or dark brown, closed cell foam.

Body: Black body wrap sparsely tied.

Tail: Black hackle strands.

Set the hook in the vice and lay down a tying silk bed including the cock hackle.

Cut a section of closed cell foam about 30mm long and 3mm by 3mm wide.

Tie in the end of the foam close to the eye and pointing beyond the eye of the hook.

Fold the foam back towards the bend of the hook and firmly tie down forming a retaining and distinct bulge in the foam at the head.

Form the body with the black body wrap and tie off.

Since the Dustbin Diver sits in the skin of the water, it is very difficult to see. Recognizing the take in any wave can be challenging.

It is usual to fish it as the tail fly in tandem with a bushy, visible fly such as a March Brown to act as an indicator.

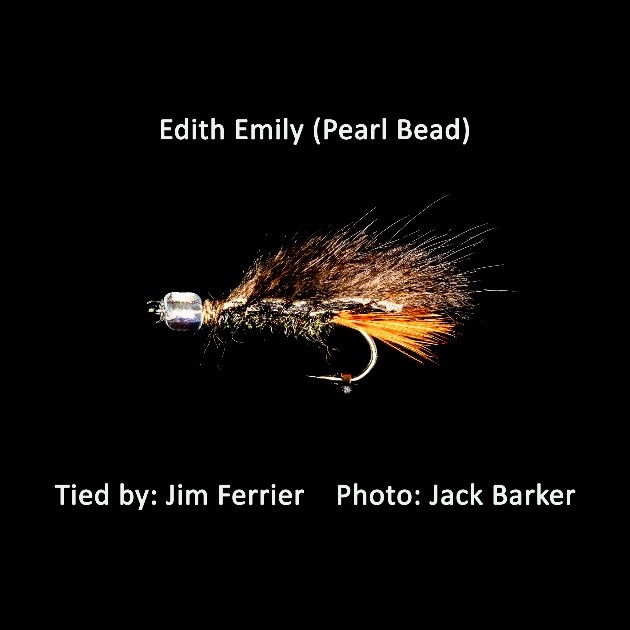

The Edith Emily.

The Edith Emily was invented to incorporate certain points which were considered vital in a fly specifically designed to attract brown trout.

This fly has proved its worth at Little Pine, the far Western Lakes and the Lilly Pond at Arthurs.

The materials had to be mobile when moving through the water and a “mink wing” and a marabou tail were used.

A contrasting of colour scheme combining black and orange was preferred, as well as the reflections of well-marked peacock herl. A pearly glass bead at the eye of the hook added weight at the front and this imparted a variation in “up and down” movement as the fly moved through the water.

The Edith Emily

Hook: Partridge low water salmon #12, #10.

Tail: Bright orange rabbit fur or marabou.

Rib: Copper wire.

Body: 3 strands rope of Peacock Herl.

“Wing”: Strip of black or brown Mink.

Significantly the glass bead being very obvious in the water, formed an “attack point” for the fish.

The preparation of the mink strip is crucial to the tying of this fly. A strip of mink of the appropriate colour is gripped in the vice and tensioned. A thin strip not more than 2mm wide cut with a very sharp scalpel from the skin side. This demands a steady and accurate hand.

The hook is taken, and the glass bead slipped round the bend and up to the eye. With the hook in the vice, the bead is held in place with a collar of tying silk.

Take the silk to the bend of the hook tying in the orange tail and the copper wire.

Tie in the peacock herl and form a rope with the tying silk and wind in neat close turns to the glass bead.

Tie in the mink strip on top of the hook shank and close behind the bead and place along the peacock herl body.

Stroke the mink fur forward towards the eye and secure against the peacock body with three or four turns of the copper wire.

Tie off and varnish.

The name “Edith Emily” was derived from the old lady of the same name who donated the first pearly beads to this fly from a very grand dress which she had had for many years.

Written by: Jim Ferrier. Flies tied by: Jim Ferrier.

Photos: Muriel Rollins and Jack Barker.

Copyright 2021 All rights reserved.